How to Influence Consumers to Behave Sustainably?

The following article was written in 2018 as a result of an independent student project supervised by the INSEAD Professor Alexandra Roulet.

In 2018, during my MBA in INSEAD, I spent a year working on an entrepreneurial project to build a second-hand good platform for students. To scale the platform, one of the critical challenges I met was the influence consumers to behave sustainably.

Addressing the ecological community seemed feasible. However, there was this question: how to incentivize mainstream users? Is it possible to rely on the willingness of people to behave sustainably just because it is better to do so for the environment?

To better understand this topic, I started working on an “Independent Student Project” in order to overview companies’ actions to influence consumers to behave in a sustainable way.

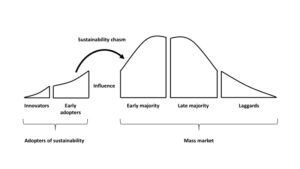

The first person I met to discuss this subject was Santiago Lefebvre (CEO and Founder of ChangeNow). In his perspective, the topic is, in reality, about how to cross the sustainability chasm.

Applying the analogy of the technology adoption lifecycle (see the book “Crossing the chasm” by Geoffrey A. Moore) to environmental impact, we could consider that today the users of sustainable products and services are comparable to the “innovators” and “early adopters”. However, to achieve mainstream customers, there is a chasm to cross. The big question is how?

Discussing with Daniel White (CEO of Signoland, co-Founder of The Behaviourlist) and Jaclyn Problete Asuncion (Decision Metrics and Finance at Climate-KIC) made me realize that crossing the chasm means changing people’s behavior and changing people’s behavior is challenging.

“It is very hard to influence people to have a sustainable behavior”,

because influencing people means influencing the system as a whole. It is about what we make available to people. If plastic is cheaper, then companies will use plastic, and consumers can’t avoid buying plastic bottles since this is what has been made available to them. Another example would be food waste: changing people’s behavior means changing the entire system.

Moreover, to change behavior, we need first to be able to measure it. Nevertheless, no survey can be a proxy of people’s behavior when it comes to environmental issues, Daniel White explained. Indeed, whenever people take environmental surveys, they present themselves as being good and not polluting.

“What they say is not what they do”, said Daniel White.

So, what can we do if it is hard to change people’s behavior regarding environmental issues?

Sustainability inertia on the demand side

First, consumers are not always aware of their everyday lifestyle’s impact on the environment. Because they are distant from environmental externalities caused, they don’t feel concerned.

Emmanuel Bardin (CEO and Founder of Lemon Tri) gave the example of someone living in a large western city, who throws a plastic bottle in the garbage in the street: it is hard for this person to imagine the negative impact this gesture has on the environment. However, this same person wouldn’t throw that plastic bottle in the Ocean because s/he is less distant from the environmental impact it would have. Nevertheless, from an ecological point of view, throwing a plastic bottle in the garbage in Paris can hurt the environment since that bottle might end up being incinerated or in the Ocean.

Next, the inertia on the demand side can be explained by how the human brain makes decisions. When people make purchasing decisions, the process is unconscious – choices are processed by the automatic mind (2) – commented Daniel White. Considering sustainable alternatives when making purchasing decisions may require a shift to the reflective mind. Therefore, cognitive biases could help people make better choices. (3)

Moreover, the sustainable products offered to consumers are often not as functional and/or esthetic as the non-sustainable equivalent one. Jaclyn Problete Asuncion gave the example of diapers that are a polluting product with no existing functional alternative: handwashing cloth diapers are not as convenient for parents as disposable diapers.

Additionally, sustainable products must be affordable and available (easy to access), and mass consumers don’t want to take the premium to purchase a sustainable product.

Finally, due to the rise of “greenwashing,” some consumers initially interested in purchasing green products became more skeptical: are they paying a premium to purchase “real green products” or is it just a marketing strategy to sell a non-sustainable product to misinformed consumers? (4)

Sustainability inertia on the offer side

Businesses are profit-maximizing oriented. The problem is that it is cheaper for companies to buy products (such as plastic) or make decisions that harm the environment than the equivalent sustainable solution. So, for such companies, maximizing shareholders’ revenues could go against minimizing the environmental impact.

While operating, if companies were forced to pay the full price of their operations – adding to their costs the social marginal one calculated by measuring the harm caused to the planet and society – their products wouldn’t be less expensive than sustainable products. Damaging the environment has a cost: the resources that nature offers for free are limited and destructible (5).

Alexandra Roulet explained that Governments act to limit pollution, either using a price approach (taxes and subsidies) and/or a quantity approach (quotas, caps, and trades) (6). Without these policies, companies do not consider the negative externalities that their polluting activities impose upon others and do not reap the full benefit of the positive externalities that their clean activities have on others.

In some European countries Governments took action, and companies transformed their business to become more sustainable and lower their environmental impact.

So, the role of public policies overcoming inertia on the offer side is very important: they have the power to shape the landscape of businesses and the long-term strategic decisions they make.

Aware that regulations will continue to evolve and that governments and NGOs will take more action increasingly in the future to protect the environment, several large companies have already started to transform their business.

Sebastien Delpont (Associate Director at Greenflex) detailed the reasons that drive companies to transform their operations to become sustainable: regulatory changes, cost reductions (example of solar panels), social status (good image), and willingness to make a positive impact on the environment.

If companies are traditionally profit-maximizing oriented, it is in their interest to change and become more sustainable-oriented.

Crossing the sustainability chasm

While during the 2008 financial crisis, the word “change” echoed hope, it became a trend ten years later. Despite the inertia on demand and offer side, environmental impact drew more attention.

NGOs started raising public awareness. Increasingly more consumers wanted to have a healthy lifestyle – no more chemicals – and preferred to change their behavior – using sharing platforms, avoiding plastic, reusing goods, etc. Increasingly more Governments reinforced regulations to protect the environment. Finally, increasingly more companies embraced sustainability and started to innovate to offer competitive and sustainable services and/or products.

Today, to go further and cross the sustainability chasm, more action from everyone is needed: more regulations from governments to influence companies’ long-term strategy and decisions, more consumers behaving sustainably, more financing of environmental projects, and more involvement from companies to stop harming the environment and greenwashing.

Companies taking sustainability actions

The concept of sustainability has evolved in recent years. Far from the costs cut and operational efficiency problems, today being sustainable means being innovative: this is the triple bottom line, where the 3Ps (People, Planet, and Profit) co-exist.

A few companies succeeded in aligning the 3Ps and took several actions to influence consumers’ behavior. For example, Patagonia is an excellent example of a company with an activist positioning: proactive active engagement in favor of environmental issues. The “Worn Wear” program encourages clients to reuse, repair, and recycle their gear.

Smallest companies tested several actions to reach mainstream consumers, through intrinsic and/or extrinsic motivations.

Influencing consumers using extrinsic motivations

Better Point, CitéGreen, or Lemon Tri used to incentivize customers to have a sustainable behavior by rewarding them with coupons that allow them to purchase items in shops. In the case of Lemon Tri – a plastic recycling company -, this business model proved to be expensive to develop and ineffective to attract mainstream consumers.

Indeed, the company developed partnerships with businesses producing sustainable products and therefore, the coupon distributed as a reward attract only ecological consumers.

Offering coupons from businesses that are not so sustainable (such as international fast food brands) would attract mass consumers. However, it would be non-sense. Unfortunately, with the coupon rewards system, Lemon Tri ended up attracting only ecological consumers interested in the company’s mission.

So, to attract mainstream users, Emmanuel Bardin, the CEO of Lemon Tri, chose to give to users a monetary reward instead of coupons. Eventually, this new business model worked well.

Influencing consumers using intrinsic motivations

Regarding intrinsic motivations to influence consumers’ behavior, no general rules can be applied; it depends on the customer companies are addressing and the products they offer.

Daniel White explained that the key is to make the message as personal and individual as possible.

For example, instead of saying this is the pollution problem in your country, companies could say this is the pollution problem in your street. Likewise, instead of saying this is the damage the chemicals make on the soils, companies should say this is the damage caused to your body.

Another motivation is the sense of belonging to a community; brands should build strong culture of collective values around sustainable issues. Mark Lee Hunter (Adjunct Professor and Senior Research Fellow at INSEAD Social Innovation Center) highlighted the importance of community building:

“People need to belong to a community with whom they share values. The sense of belonging creates a strong relationship between customers and the brand”.

How to reach mainstream customers when selling sustainable products? Mark Lee Hunter also explained that the starting point is the people who are already onboarded.

Indeed, it is possible to either build a new community or join an existing one, but not to change it. He added that when starting a business, “companies should explore the existing communities around their niche, and monitor their insights into competitors and the company’s products.

Flaws need to be corrected immediately because reputations can be swiftly damaged within communities whose members know and trust each other. Companies must watch the perceived value of their offerings within these communities”.

Conclusion: How can companies influence consumers to behave sustainably?

Human actions have harmed the environment since the industrial revolution. Acting to lower the human footprint is a necessity. Because it is a collective problem, everyone should take responsibility for finding solutions: consumers, companies, investors, governments, and NGOs.

Some companies decided to develop sustainable products and services to protect the environment. Then, reaching mainstream customers is a challenge because it means influencing people’s behavior, and therefore, the whole system.

To cross the sustainability chasm, companies should better

- improve their products to make them more functional and/or esthetic,

- innovate their business model to align the 3Ps (People, Planet, and Profits),

- build a culture of collective values around sustainability,

- incentivize customers through extrinsic (monetary, points, coupons, etc.) or intrinsic motivations.

For the latter, even if no general rule can be applied, it is important when raising awareness, to make the information as customized as possible and involve the consumer at a personal level.

Interviewees, Footnotes and References

Interviewees:

- Alexandra Roulet: Assistant Professor of Economics in INSEAD

- Mark Lee Hunter: Adjunct Professor and Senior Research Fellow at INSEAD Social Innovation Center

- Santiago Lefebvre: CEO and Founder of ChangeNow

- Daniel White: CEO of Signoland co-Founder of The Behaviourlist

- Jaclyn Problete Asuncion: Decision Metrics and Finance at Climate-KIC

- Emmanuel Bardin: CEO and Founder of Lemon Tri

- Sebastien Delpont: Associate Director at Greenflex

Footnotes:

(1) United Nations, Framework Convention on Climate Change: https://bigpicture.unfccc.int

(2) The automatic mind the concept explained by Daniel Kahnemann

(3) According to the study “Mindspace, influencing behavior through public policy”, (see reference below), changing behavior requires understanding the two systems operating in the brain: the reflective and the automatic:

« These two approaches are founded on two different ways of thinking. Psychologists have recently converged on the understanding that there are two distinct, systems “operating in the brain”. The two systems have different capabilities: the reflective mind has limited capacity, but offers more systematic and “deeper” analysis. The automatic mind processes many things separately, simultaneously, and often unconsciously, but is more “superficial”: it takes short-cuts and has ingrained biases. As one academic source explains, “once triggered by environmental features, [these] preconscious automatic processes run to completion without any conscious monitoring”.

In practice, this distinction is not so clear-cut: a mix of both reflective and automatic processes govern behaviour. When reading a book, for example, we can concentrate and ignore our surrounding environment – but if someone calls our name, we break off and look at them. Our reflective system is ignoring everything but the book, but our automatic system is not. Policy-makers attempting to change behaviour need to understand how people use these different systems and how they affect their actions. »

(4) Environmental Quality Management. Winter2008, Vol. 18 Issue 2, p71-78. 8p, by Bergeson, Lynn L.

(5) For further information, read the article, “The sustainable economy”, by Yvon Chouinard, Jib Ellison, and Rick Ridgeway

(6) Alexandra Roulet, Public Policy course (subject: climate change)

References:

- www.changenow-summit.com

- Crossing the chasm, author Geoffrey A. Moore

- The sustainable economy, by Yvon Chouinard, Jib Ellison, and Rick Ridgeway

- Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report, by Rajendra K. Pachauri (Chairman IPCC)

- Companies Are Working with Consumers to Reduce Waste, by by Mark Esposito, Terence Tse and Khaled Soufani

- Mindspace, influencing behavior through public policy, by Paul Dolan, Michael Hallsworth, David Halpern, Dominic King, and Ivo Vlaev

- United Nations, Framework Convention on Climate Change: https://bigpicture.unfccc.int

- https://alimentation-generale.fr/en-continu/danone-se-fixe-lobjectif-de-zero-emissions-de-carbone-nettes-dici-a-2050/

- https://www.businessinsider.com/adidas-parely-ultra-boost-womens-review?IR=T

- https://www.patagonia.com

- https://lemontri.fr

- https://www.betterpoints.uk